DOI: 10.17545/e-oftalmo.cbo/2016.61

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: To present a clinical report of patients with prelenticular leukocoria.

METHODS: retrospective study included patients with an initial diagnosis of unilateral leukocoria referred for pediatric cataract surgical treatment during the period between 2005 and 2015 at São Paulo-SP, Brazil. Complete ophthalmological evaluation was performed.

RESULTS: Seven patients younger than 4 years were evaluated to determine the need for cataract surgery. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy evaluation disclosed two patients with juvenile xanthogranuloma and inflammatory pupillary membrane, threewith secondary inflammatory pupillary membrane caused by idiopathic anterior uveitis, one with prelenticular leukocoria due to presumed congenital toxoplasmosis, and one with an inflammatory membrane due to repeated hyphema caused by iris hemangioma. In all these cases, ultrasonographic examination did not show retinal or lens abnormalities in the affected eye.

CONCLUSION: All patients presented unilateral prelenticular leukocoria with clear lens, requiring no cataract removal.

Keywords: Child: Cataract: Classification: Retinoblastoma

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: apresentar um relatório clínico de pacientes com leucocoria pré-cristaliniana.

MÉTODOS: estudo retrospectivo incluindo pacientes com diagnóstico inicial de leucocoria unilateral e encaminhados a tratamento cirúrgico de catarata, entre 2005 e 2015, na cidade de São Paulo (SP), Brasil. Realizou-se avaliação oftalmológica completa.

RESULTADOS: sete pacientes, com menos de 4 anos de idade, foram avaliados para se determinar a necessidade da cirurgia de catarata. A avaliação através de biomicroscopia (lâmpada de fenda) revelou dois pacientes com xantogranuloma juvenil e membrana pupilar inflamatória, três com membrana pupilar inflamatória secundária causada por uveíte anterior idiopática, um com leucocoria pré-cristaliniana possivelmente devido a uma toxoplasmose congênita, e um com uma membrana inflamatória devido a hifema recorrente causado por hemangioma da íris. Em nenhum desses casos o exame ultrassonográfico revelou anormalidades na retina ou na lente do olho acometido.

CONCLUSÃO: todos os pacientes apresentaram leucocoria pré-cristaliniana unilateral, com lentes translúcidas, sem necessidade de remoção de catarata.

Palavras-chave: Criança: Catarata: Classificação: Retinoblastoma

INTRODUCTION

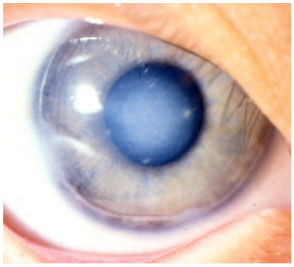

Presence of leukocoria or abnormal red-reflex test in children needs prompt evaluation and diagnosis (Figure 1). Retinoblastoma can be diagnosed and it is a life-threaten disease. 1,2,3

Leukocorias can be classified in two major groups: lenticular leukocorias (lens opacification) and retrolenticular leukocorias (retinoblastomas or pseudo-retinoblastomas). 4

This study aims to present the clinical description of patients with unilateral leukocoria without lens opacification and to refer a proposed classification of leukocorias including cases with prelenticular opacifications.5

METHODS

This is a descriptive and retrospective study comprising patients referred for cataract surgery owing to an abnormal red reflex test and unilateral leukocoria in the affected eye. In this study, leukocoria was defined as visual axis opacification with a white pupil and abnormal red reflex (Bruckner test).

Ophthalmological evaluation, including slit-lamp examination, visual acuity, binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy, and ocular ecography, was performed for all patients.

Case 1

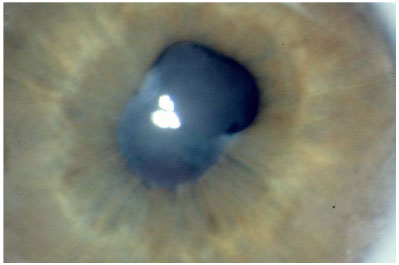

A 3-month-old male presented with an abnormal red reflex test and unilateral leukocoria in the right eye. Visual acuity was LogMAR 1.30 (Snellen 20/395) in the affected (right) eye and LogMAR 0.67 (Snellen 20/95) in the normal eye. Slit-lamp examination disclosed a prelenticular membrane at the pupillary area, posterior synechiae and no lens opacification (Figure 2). Ultrasound was normal. Clinical diagnosis revealed a prelenticular membrane caused by idiopathic anterior uveitis.

Case 2

A 3-month-old girl showed unilateral leukocoria in the left eye. Her mother had developed active, systemic toxoplasmosis during pregnancy. Visual acuity was LogMAR 0.120 (Snellen 20/250) in the affected eye. Slit-lamp examination showed fibrin tissue over the pupillary edge with posterior synechiae and a clear lens. Intraocular pressure was normal in both the eyes. Ophthalmoscopy disclosed an isolated and possible congenital toxoplasmosis scar (without inflammatory activity at the peripheral retina. Ultrasound failed to show acoustic activity in the posterior section of the eye globe. The clinical diagnosis was prelenticular leukocoria caused by fibrin tissue formation over the pupillary edge and posterior synechiae formation, probably related to congenital toxoplasmosis.

Case 3

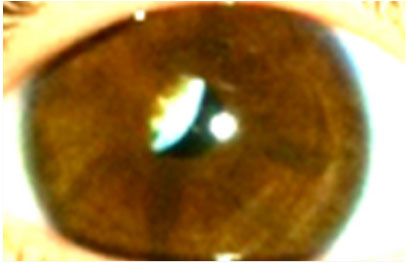

A 3-year-old boy presented with leukocoria in the right eye. The patient had a previous trabeculectomy surgery due to glaucoma related to juvenile xanthogranuloma. His best visual acuity was LogMAR 0.86 (Snellen 20/145) in the affected eye. External examination disclosed yellowish dermatological lesions on the face, thorax (Figure 3), and both lower limbs. Slit-lamp evaluation showed buphthalmos, a superior filtering bubble; yellowish nodules in the iris, a partial prelenticular membrane at the pupillary area; and a clear lens (Figure 4). Intraocular pressure was 5 mmHg in both eyes. Indirect ophthalmoscopy and ultrasound were normal. The clinical diagnosis was a prelenticular membrane, secondary to anterior chamber hyphema, caused by juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Case 4

A 6-month-old girl presented with leukocoria in the left eye. Her visual acuity was light perception in the affected eye. Slit-lamp examination showed yellowish nodular lesions in the iris and a thick membrane formation across the pupillary area, preventing lens observation. Surgery was performed by anterior chamber removal of the pupillary membrane, revealing a clear lens underneath. Anatomopathological analysis of the specimen revealed a fibrin membrane. A spontaneous anterior chamber hemorrhage occurred within 20 days of the procedure. The hyphema improved with clinical treatment but relapsed again after 3 months. The clinical diagnosis was a prelenticular membrane secondary to bleeding from the juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Case 5

A 14-month-old boy presented with unilateral leukocoria in the left eye. His visual acuity was LogMAR 1.45 (Snellen 20/415). Slit-lamp examination showed a prelenticular membrane affecting the pupillary area and no red reflex. Ultrasound showed a normal posterior vitreous cavity. The clinical diagnosis was an idiopathic prelenticular membrane. A membranectomy was performed and revealed a clear lens. Eight months after the surgical procedure, visual acuity improved to 20/40.

Case 6

A 3-year-old girl presented with leukocoria in the left eye. Her visual acuity at presentation was LogMAR 0.60 (Snellen 20/80). Slit-lamp examination disclosed a prelenticular membrane with a partially occluded visual axis (Figure 5). The opaque membrane remained stable during the follow-up. No surgical treatment was performed on this patient. Indirect ophthalmoscopy and ultrasonography were both normal. The clinical diagnosis was unilateral leukocoria due to prelenticular membrane formation, probably after idiopathic anterior uveitis.

Case 7

A 2-month-old girl presented with facial hemangioma affecting the right eyelid area. She was referred with leukocoria in the right eye. Visual acuity was LogMAR 1.45 (Snellen 20/570). Slit-lamp examination showed multiple nodular lesions in the iris, compatible with iris hemangioma. A prelenticular membrane, partially affecting the visual axis, and a clear lens were observed. Ophthalmoscopy and ultrasound examinations were normal. The clinical diagnosis was unilateral leukocoria with a prelenticular membrane secondary to iris hemangioma. The membrane could be as result of repeated anterior chamber hyphema.

RESULTS

Seven patients with unilateral leukocoria were referred for cataract surgery. All were aged <4 years. After complete ophthalmological examination, the clinical findings in all patients revealed no lens opacification. All children presented with unilateral prelenticular leukocoria. All cases had normal indirect ophthalmoscopy and posterior segment ultrasonography in the affected eye.

The ophthalmological findings of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Leukocoria is an important sign of several pediatric ophthalmological conditions. It is a dangerous situation demanding immediate attention because many of the affected children may have pathologies that either threaten life or can cause permanent visual disability. Leukocorias are related to congenital cataract, retinoblastoma, ocular toxocariasis, toxoplasmosis, retinopathy of prematurity, retinal hamartomas, persistent fetal vasculature, Coats' disease, retinal detachment, Norrie disease, and intraocular hemorrhage. 6,1

Leukocoria or “white pupil” is an eye disorder. Leukocoria, in its strictu sense is a term used only in patients with an abnormal red reflex test when its cause is located behind the lens. 8 In this study, leukocoria was broadly defined because it is frequently used in ophthalmology as any ocular disturbance in the red reflex test. This broad definition includes patients with circumscribed central corneal scars affecting the visual axis and the red reflex test.

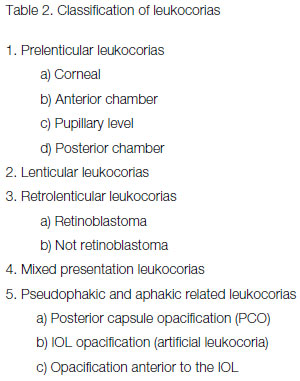

A new classification for the leukocorias, which includes prelenticular findings, was previously noted. This novel classification includes cases with prelenticular leukocoria and leukocoria with mixed presentation. 9

We presented seven patients with unilateral leukocoria caused by prelenticular opacification. Cataract and retinal abnormalities were not diagnosed in this group of patients. We presented three patients with a pupillary membrane caused by idiopathic anterior uveitis,two with juvenile xanthogranuloma, one with intraocular hemangioma, and one with presumed congenital toxoplasmosis. In two patients, the leukocoria was present due to membrane formation after hyphema.

There are other causes of prelenticular leukocoria, including the presence of persistent congenital pupillary membrane, especially in patients with a blue iris, and that of central circular corneal leukoma (Figure 6) affecting the visual axis. 9 Identification of prelenticular leukocoria allows a surgical strategy plan to avoid unnecessary lens removal. Early achievement of a clear visual axis is of great importance for prevention of amblyopia in children with prelenticular leukocoria. Use of anterior chamber ultrasonic biomicroscopy is helpful for an accurate diagnosis of prelenticular leukocorias as well as to better identify patients with a clear or opacified lens.

Prelenticular leukocorias can be divided according to the location of the opacity: corneal, anterior chamber, pupillary level, and posterior chamber.

Some patients may present with prelenticular leukocoria associated with lens opacification; for example, an inflammatory pupillary membrane associated with cataract. The association of prelenticular and retrolenticular leukocoria can occur in cases of persistent fetal vasculature, retinoblastoma, Coats' disease, etc. These cases are classified as mixed presentation leukocorias.

Visual axis opacification may be present in pseudophakic or aphakic eyes, causing leukocoria. They are classified as pseudophakic-and aphakic-related leukocoria. The proposed classification of leukocorias is displayed in Table 2.

REFERENCES

1. Balmer A, Munier F. Diagnosis and treatment of intraocular tumors in the child. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2001 ;218(5):292-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2001 -15884

2. Balmer A, Munier F. Leukokoria in a child: emergency and challenge. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1999;214(5):332-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1034807

3. Shields JA, Parsons HM, Shields CL, Shah P. Lesions simulating retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1991;28(6):338-40.Abstract disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=PMID%3A+1757860

4. Gao YJ, Qian J, Yue H, Yuan YF, Xue K, Yao YQ. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of children with intraocular retinoblastoma: a report from a Chinese cooperative group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.23002

5. Tartarella MB, Britez-Colombi GB, Fortes Filho JB. Proposal of a novel classification of leukocorias. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:991-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S31469

6. Servodidio CA, Abramson DH. Coats' disease. Insight. 1996;21 (4):112-3. Abstract disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=PMID%3A++9392769

7. Abramson DH, Servodidio CA. Retinoblastoma in the first year of life. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1992;13(4):191-203. Abstract disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=PMID%3A+1488219

8. Moshfeghi DM, Wilson MW, Haik BG, Hill DA, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Pratt CB. Retinoblastoma metastatic to the ovary in a patient with Waardenburg syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(5):716-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01352-1

9. Kolin T, Murphee AL. Hyperplastic persistent pupillary membrane. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(6):839-41 .Abstract disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=PMID%3A+9535632

Funding source: None

Conflicts of interest: None

Received on:

October 1, 2016.

Accepted on:

October 11, 2016.