Carlos Augusto Moreira Neto1; Carlos Augusto Moreira Júnior2

DOI: 10.17545/e-oftalmo.cbo/2015.32

ABSTRACT

Here, we describe an adult male with extensive drusen-like deposits in both eyes, rapidly progressing to extensive {2.1 [EN] Verify English word/phrase choice} macular atrophy. A fully documented eight-year clinical history, with fundus images, has been reported, and although macular atrophy may resemble atrophic age-related macular degeneration, it can be distinguished by some striking features, including extensive drusen-like deposits in the posterior pole of both eyes, vertical macular atrophy, and rapid deterioration of visual acuity in patients under 50 years of age.

Keywords: Vision-screening programs. Ophthalmological diagnostic techniques. Children. Ocular refraction.

RESUMO

Este estudo relata o caso de um paciente adulto com depósitos tipo drusen em ambos os olhos, evoluindo rapidamente para atrofia macular extensa. A história clínica foi documentada na íntegra por oito anos com imagens de fundo de olho e, embora semelhante à degeneração macular atrófica relacionada à idade, a atrofia macular pode ser distinguida por características marcantes como depósitos extensos do tipo drusen no polo posterior de ambos os olhos, atrofia macular vertical e deteriorização da acuidade visual em pacientes com idade inferior a 50 anos.

Palavras-chave: Programas de Rastreamento. Técnicas de Diagnóstico Oftalmológico. Crianças. Refração Ocular. Ambliopia.

INTRODUCTION

Macular atrophy is a retinal complication that may lead to severe visual impairment and can have different causes, such as inflammation, intoxication, hereditary conditions, and predominantly, age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The course of macular atrophy in AMD has been well documented 1,2,3,4. Following the appearance of drusen-like deposits, small areas of atrophy occur in the perifoveal region. Such areas tend to be confluent over the years and follow the disappearance or flattening of soft drusen3,4,5. Usually, macular atrophy does not extend beyond the perifoveal area; however, some patients may develop it in the late stages of the disease, becoming legally blind by the age of 70 years or older.

Here, we present a case of macular atrophy in a 50-year-old male who was followed up for 8 years because of drusen-like deposits in the posterior pole of both eyes. Although it may resemble atrophic AMD, macular atrophy has a distinct clinical appearance, and this was described by Hamel et al.6 in 2009 as a new clinical entity. The prominent features include the early onset of bilateral, symmetric macular atrophy, typically before the age of 50 years, with a rapid involvement of the fovea and the entire posterior pole up to the temporal vascular arcades6.

CASE REPORT:

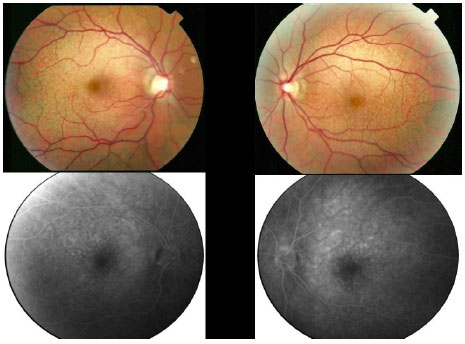

In 2007, a 43-year-old white man sought ophthalmic care, for poor vision. Visual acuity (VA) was measured as 20/20 OU with a correction of -7,00 D. The intraocular pressure was 13 mmHg, and a color fundus image revealed drusen-like deposits in the posterior pole of both eyes. Fundus fluorescein angiographies were performed, demonstrating drusen-like deposits in both eyes (Figure 1). The patient was prescribed oral antioxidants and vitamins, according to the Age-Related Eye Disease Study formulation.

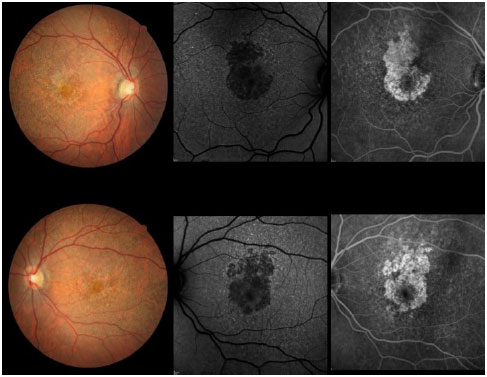

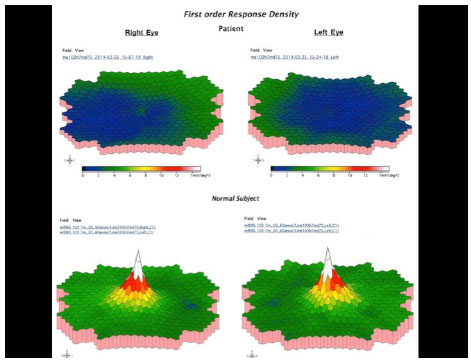

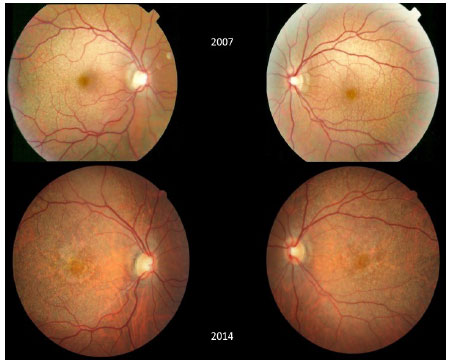

In 2012, he was re-examined at another clinic, presenting with the same vision and complaints. Color fundus images taken during that visit were subsequently sent to us. In the beginning of 2014, he experienced a severe loss of his vision and came back for a new examination, which revealed VA as 20/200 OD and 20/60 OS. An area of atrophy was observed in the foveal and perifoveal regions along with areas of paving-stone degeneration in the far periphery of both eyes. Color retinography, autofluorescence, and fundus fluorescein angiography were performed, demonstrating a definite area of macular atrophy in both eyes with a larger vertical diameter (Figure 2). Multifocal electroretinography (ERG) showed a severe decrease in the cone function of both eyes (Figure 3). Full-field ERG was normal.

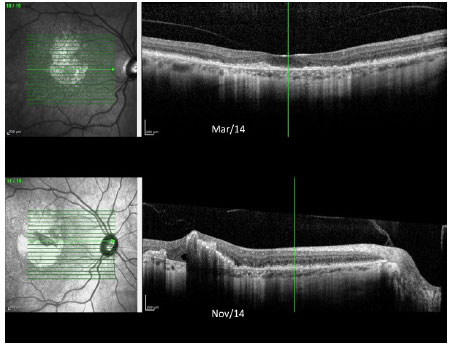

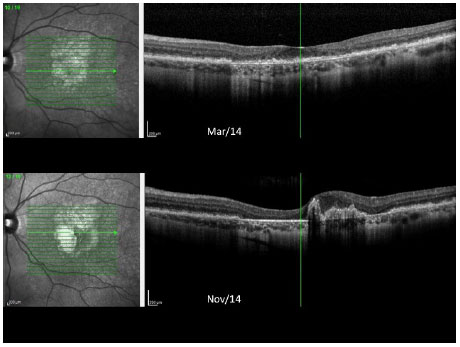

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed a macular thinning in the atrophic area, with foveal central thickness measuring less than 200 µ.

At this time, the patient’s chief complaint was related to his distance vision. He claimed that he could still read without glasses because of the high myopic error, and he needed a bright light to accomplish near-distance tasks. He had no problems concerning light adaptation and did not complain of photophobia. However, the color vision was severely affected. A central scotoma was present in the visual fields of both eyes.

In the following months, his vision rapidly deteriorated, and in October 2014, VA was 20/200 OU. Reading could be achieved only with low vision aids.

Color fundus images of both eyes during the follow up are shown in Figure 4. OCT images of both eyes taken over the past year are shown in Figures 5 and 6.

DISCUSSION:

As the technology advances and our knowledge about AMD increases, we will be able to identify different forms of macular diseases occurring in adulthood. Recently, Hamel et al.6 described a form of macular atrophy that occurs earlier than AMD. Although macular atrophy resembles AMD, they described it as a new clinical entity with features that are different from those of AMD. The main features include extensive {1.5 [EN] Verify technical word choice} macular atrophy, with a larger vertical diameter, occurring around the age of 50 years along with pseudodrusen deposits affecting the entire posterior pole and paving-stone degeneration in the retinal periphery.

Hamet et al. have described 18 patients with complaints of rapid visual loss, night blindness, and central scotoma in a group of patients around 50 years of age. The rapid onset of visual loss and macular atrophy were striking characteristics. Probably, many of these patients were previously diagnosed with a precocious type of AMD. The work of Hamel et al.6 has led us to consider such a retinal disease as a new clinical entity, and its specific features and clinical course should be identified in order to appropriately manage such patients.

Therefore, adult patients with drusen-like deposits in the posterior pole of both eyes may have a clinical course different from those with regular drusen deposits in the macular area. According to our observations, these patients rapidly progress to central visual loss, becoming legally blind by the age of 50 years. All other features, previously described by Hamel et al.6 were observed in the present case, including extensive macular atrophy in both eyes with a larger vertical diameter, central scotoma, drusen-like deposits in the posterior pole, color vision deficit, paving-stone degeneration in the retinal periphery, focal ERG showing a severe decrease in cone function, and rapid deterioration of central VA.

Although no treatment is currently available for this disease, it is important to identify this clinical entity in order to avoid confusion with AMD in patients at a younger age.

REFERENCES

1 klein ML, Ferris FL, Armstrong J. et al. AREDS Research Group. Retinal precursors and the development of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degenerations. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1026-1031.

2 Arnold JJ, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP. Reticular pseudodrusen. A risk factor in age-related maculopathy. Retina 1995;15:183-191.

3 Schatz H, McDonald HR. Atrophie macular degeneration. Rate of spread of geographic atrophy and visual loss. Ophthalmology 1989; 96:1541-1551.

4 Sunness JS, Gonzalez-Baron J, Applegate CA, et al. Enlargement of atrophy and visual acuity loss in the geographic atrophy form of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 1999;106:1768-1779.

5 Sunness JSA, Margalit E, Srikumaran D, et al. The long-term natural history of geographic atrophy from age-related macular degeneration: enlargement of atrophy and implications for interventional clinical trials. Ophthalmology 2007;114:271-277.

6 Hamel CP, Meunier I, Arndt C, et al. Extensive macular atrophy with pseudodrusen-like appearance: a new clinical entity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(4):609-20.

Comments:

Dr. Sergio Gianotti Pimentel

Chefe do Setor de Retina, Departamento de Oftalmologia, USP. sergiopimentel19@amail.com

In this paper, the authors present an interesting case of bilateral, symmetric, and progressive macular atrophy associated with extensive drusen-like deposits in a middle-aged male, compatible with the diagnosis of extensive macular atrophy with pseudodrusen-like appearance (EMAP), recently reported by Hamel et al.1

In 2009, Hamel et al.1 reported the first series of 18 EMAP cases, representing a new clinical entity. Patients initially presented with dark adaptation complaints, central scotoma, and decreased near vision; later, decreased far vision followed along with a loss in bilateral central vision. The patients had previously been diagnosed with uncharacteristic macular dystrophy, before the age of 50 years, in the absence of a family history. The mean age at onset was 47 years (range, 41-54 years), 11/18 were women, and myopia was present in 14/18 patients. Mean initial visual acuity (VA) was 20/100 (light perception of 20/20), and final VA was reduced to 20/200 in all eyes except for one. Anterior segment examinations were unremarkable. Other EMAP case series were later reported by Querques et al.1 and Kamami-Levy et al.3

In summary, EMAP was diagnosed by the following characteristics: 1,2,3 1. bilateral and symmetric macular atrophy with a larger vertical diameter; 2. rapid involvement of the posterior pole and the fovea; 3. early onset (age <55 years); 4. numerous pseudodrusen-like deposits in the posterior pole and at the equator; 5. paving-stone degeneration, predominantly in the inferior or temporal peripheral retina.

The pseudodrusen-like deposits were described as “numerous yellowish, poorly contrasted, flat spots at the posterior pole, which look like drusen.”.6 Optical coherence tomography demonstrated no nodular thickening of the pigment epithelium —Bruch membrane complex. These spots were hypofluorescent on autofluorescence images and were not visible by fundus fluorescein angiography.1 Kamami-Levy et al.3 found that choroidal neovascularization may be present in almost 10% EMAP eyes (4 out of 38 eyes).3

The main differential diagnosis is advanced age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with geography atrophy (GA). GA appears after 50 years, with slow progression of small foci, usually after drusen regression, a larger horizontal diameter, and is related to environmental and genetic risk factors.4 Ferrara et al. recently described the phenotypic presentation associated with complement factor H R1210C mutation, a rare variant, strongly associated with soft drusen accumulation in the macula, as well as with rapid advanced AMD with GA.5 However, in EMAP, patients are younger than 50 years and exhibit a faster progression of atrophy with a larger vertical diameter and without drusen formation.1,2

EMAP have features that differ from similar retinal dystrophies.1,6 Absence of pigment deposits in the macula, equator, or in the periphery, normal retinal vessels, ERG responses are only moderately decreased, no peripheral visual loss, no evidence of a familial heredity, and characteristic retinal lesions differentiate EMAP from cone dystrophies and cone-rod dystrophies.7 These features also differentiate EMAP from autosomal dominant macular dystrophies, such as Sorsby’s fundus dystrophy,8 North Carolina macular dystrophy,10 and central areolar choroidal dystrophy,9 and from late-onset macular retinal degeneration.11 An important limitation in the description of EMAP as a clinical entity is the lack of genetic screening.6 A better characterization of genetic profiles in EMAP patients will provide a better understanding of its pathogenesis and possible future treatments of this vision-threatening condition.

REFERENCES

1 Hamel CP, Meunier I, Arndt C, et al. Extensive macular atrophy with pseudodrusen-like appearance: a new clinical entity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(4):609-20.

2 Querques G, Blanco R, Puche N, Massamba N, Souied EH. Extensive macular atrophy with pseudodrusen-like appearance. Ophthalmology 2013;120:429 e1-e2.

3 Kamami-Levy C., Querque G., Rostaqul O., Blanco-Garavito R., Souied E.H. Choroidal neovascularization associated with extensive macular atrophy with pseudodrusen-like appearance. Journal français d'ophtalmologie 2014;37:780-86.

4 Sobrin L, Seddon JM. Nature and nurture: genes and environment predict onset and progression of macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2014;40: 1 -15.

5 Ferrara D, Seddon JM. Phenotypic Characterization of Complement Factor H R1210C Rare Genetic Variant in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133(7):785-91.

6 Boon CJ, Theelen T, Hoyng CB. Extensive macular atrophy with pseudodrusen-like appearance: a new clinical entity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Jul;148(1 ):173-4; author reply 174-5.

7 Michaelides M, Hardcastle AJ, Hunt DM, Moore AT. Progressive cone and cone-rod dystrophies: phenotypes and underlying molecular genetic basis. Surv Ophthalmol 2006; 51:232-258.

8 Gliem M, Müller PL, Mangold E, Holz FG, et al. Sorsby Fundus Dystrophy: Novel Mutations, Novel. Phenotypic Characteristics, and Treatment Outcomes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(4):2664-76.

9 Khurana RN, Sun X, Pearson E, Yang Z, et al. A reappraisal of the clinical spectrum of North Carolina macular dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(10):1976-83.

10 Smailhodzic D, Fleckenstein M, Theelen T, Boon CJ, et al. Central areolar choroidal dystrophy (CACD) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD): differentiating characteristics in multimodal imaging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(12):8908-18.

11 Borooah S, Collins C, Wright A, Dhillon B. Late-onset retinal macular degeneration: clinical insights into an inherited retinal degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:284-289.

Funding source: None declared.

Conflict of interest: The author declares to have no conflicts of interest.

Research Ethics Committee Opinion: N/A.

Received on:

August 3, 2015.

Accepted on:

September 3, 2015.