Sidney Julio Faria-e-Sousa1; Gleilton Carlos Mendonça2; Gustavo Victor3

DOI: 10.17545/e-oftalmo.cbo/2015.26

ABSTRACT

This article aims to provide the beginner ophthalmologist with basic information on audiovisual communication techniques with slides, to help create objective, creative, and effective presentations.

Keywords: Audiovisual Communication. Scientific Presentation. Slide Show. Use of Slides.

RESUMO

O objetivo deste trabalho é fornecer ao oftalmologista iniciante informações básicas sobre a técnica de comunicação audiovisual com slides, de forma a ajudá-lo a criar apresentações objetivas, criativas e eficazes.

Palavras-chave: Comunicação Audiovisual. Apresentação Científica. Apresentação de Slides. Uso de Slides.

INTRODUCTION

Ophthalmic diagnostic techniques have greatly evolved over the past 20 years. Notably, these improvements have become increasingly accessible to physicians in daily practice.

Among several implications of this phenomenon, the role of ophthalmologists is changing: they are not only service providers but also major knowledge generators. Thus, their participation in scientific meetings as speakers has increased. The scientific literature has a vast amount of information on written communication, but is scarce with regard to oral communication of knowledge. This is an issue for the novice speaker. A probable explanation of this scenario is the misconception that oral communication requires no theoretical basis; what matters is the common sense and natural aptitude of the speaker. It is the philosophy of the long-haul drivers, who use their vehicles with such frequency and relaxation that they are unaware of the traffic laws and violations. When faced with proposals such as “defensive driving,” they reject them with contempt. For them, practice is the only thing that matters; everything else is digression.

This article aims to provide the beginner ophthalmologist with basic information on audiovisual communication techniques with slides, to help create objective, creative, and effective presentations.

PILLARS OF ORAL PRESENTATION

Six topics are considered in the preparation of an oral presentation: audience, logistics, subject, creativity, endogenous competition, and posture. Each of them will be described in detail.

I. AUDIENCE

The first information that the lecturer should gather is the nature of the audience, which can range from laypeople to highly specialized academics. For effective communication, it is essential that the language and complexity of the subject are adapted to the audience. Overly fancy language, with excessive details and medical jargon, has less chance of holding the attention of lay audience. Conversely, informal language with superficial and imprecise concepts tends to not please the more educated ears.

The most difficult situation is when the audience is heterogeneous, e.g., the professional who is invited to speak regarding corneal transplants for a group of physicians and laypeople. Explaining that the cornea resembles glass clock favors the laypeople, because the analogy helps them to understand the anatomy of the eye, but distracts physicians, for whom the comparison is overly simplistic. The solution to this impasse is to grade the language and content for those less familiar with the subject, and explain to the rest of the audience that this option is being used for the benefit of all. People usually accept this explanation without conflict. If the lecture is good, they will consider it as a model for their own presentations.

II. LOGISTICS

The second concern should be the resources available for the presentation. It is important to have prior knowledge of the location: the living room, patio, or clubroom. For instance, it may be impossible to present slides simply because it is not dark enough. The board may not fit on the stage or the projector’s cord may not reach the electrical outlet.

If a board is used, the speaker should bring his/her own chalk or marker. If a computer is used, it is necessary to arrive well before the event begins to circumvent the inevitable software and hardware conflicts. Whenever possible, the creation of digital presentations with the latest software version available for this purpose should be avoided. If the version used is newer than that installed on the local computer, the data may not be readable. Computer science is the reign of Murphy's law: "If something can go wrong, it will go wrong.”

III. SUBJECT

The basic assumption regarding a lecturer is that he/she knows the subject very well. Thus, the speaker should seek information from various sources because the plurality of information encourages critical judgment, a key element for unveiling the “essence of the matter.” Each subject has an essence, a basic message. This message needs to be extracted and transmitted in an objective and understandable manner. Knowing this information, the listener decides whether or not to delve into the subject by searching out new sources.

We live in a time when the speed of information creation is greater than the ability of an individual to absorb it. Therefore, we are forced to be selective. The ability to synthesize is a process that is developed slowly with training. In an exchange of correspondence between two mathematicians of the 17th century, one of them has written the following: “I would have written a shorter letter, but I did not have the time.”

IV. CREATIVITY

It is with creativity that we bring life and personality to the presentation, marking our presence as thinking, communicative beings. A pleasant way to practice creativity is to exercise the habit of discovering the unexplored side of everything that is read or seen.3 For example, if the subject is usually shown from the clinical side, one should try to explore its pathophysiological mechanisms; if it is usually presented in theoretical aspects, its practical value should be unraveled. Always search for new information that will enrich the topic; furthermore, never completely repeat the same oral presentation.

However, it is necessary to remember that boldness can bring both glory and misfortune. Creativity requires sharpened critical thinking. Therefore, very unconventional ideas or information should be viewed with suspicion. They should only be accepted after careful reflection. To do so, do not hesitate to request for the help of specialists in the subject; they are usually happy to help, as it provides them with a sense of usefulness.

V. ENDOGENOUS COMPETITION

At an oral presentation, the main vehicle of communication is speech. Texts and figures are auxiliary features that help to sort and synthesize ideas. The downside of these aids is that they tend to compete with the speaker for the audience’s attention. They create an endogenous competition. When it occurs, the audience is torn between what they hear and what they see, which hinders the assimilation of information. The most effective ways to avoid it are the judicious control of the number of slides and simplification of their contents. The following are nine suggestions to minimize endogenous competition:

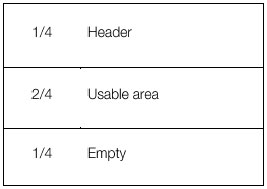

1. Do not clutter the slides. A cluttered slide presents excessive information. When it is very difficult to interpret, it steals the listener's attention. The solution is to reduce the amount of data on the slide. This can be achieved in two ways: using only the most important data or dividing the information into multiple slides, under one heading. A strategy to condition oneself into working with uncluttered slides is to divide the slide into four identical horizontal areas. The top should be used for the header and the lower section should be left empty, restricting the information to the two central areas (Figure 1).

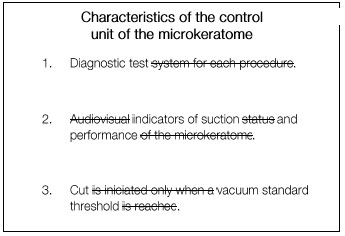

2. Avoid complete sentences. On slides, the text should be used as a reminder or an index. Briefly, they should contain as few words on each line as possible (Figure 2). Complete sentences demand more attention, and therefore, stimulate competition between the speaker and the slide. Converting whole sentences into a few words, without losing the original meaning, is probably the greatest challenge in constructing a slide.

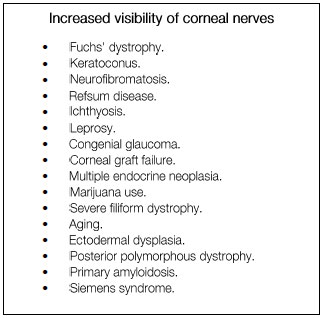

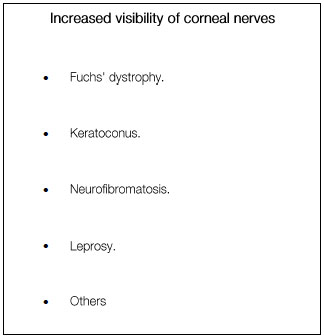

3. Avoid long lists. If the list of items is very large to fit on a single slide, the first question to be asked is whether it is necessary to present that much information (Figure 3). In most cases, the message can be summarized through a judicious selection of data (Figure 4). When pedagogy conflicts with precision, it is usually more effective to favor the first. In rare situations where all information is essential, the list can be divided into more than one slide with the same header. The important point is that everything is legible.

4. Beware of tables. Tables should only be presented in slides when their content is easily identifiable. Therefore, they have to be small, with clearly visible data. When this is not possible, it is better not to include a table.

5. Beware of figures. A picture is worth a thousand words. However, in slides, this only tends to be true when the figure is simple. The lecturer should always check that the figures are not too complex or cluttered with details. Similar to tables, if the figure is complex, it can be distributed across multiple slides with the same header.

6. Choose the fonts carefully. Sans serif fonts, which are easier to read, should be preferred. The text should not be written with all the words in all caps because it appears to be a “shouted” message. The font size should not be very small, such that it is difficult to read, but not very big, such that it appears that the audience is visually impaired. In the authors’ experience, a 20- to 24-point font is enough to ensure good readability of text; a 28- to 32-point font is sufficient to highlight the header. Row spacing should be at least 1.5 times the font size.

7. Avoid distracting backgrounds. The slide background should not hamper the identification of what is written or drawn on it. Furthermore, it should not to be overly attractive. Both situations compete with speech for the attention of the audience.

8. Contain extravagant tendencies. Colors can either help or hinder the presentation. When excessive, they tend to draw attention negatively, reflecting extravagance and amateurism. Ideally, no more than three colors should be used; they should harmonize to transmit sober and pleasant impressions.

9. Beware oftext-image redundancy. This phenomenon is common in sessions in which text and images are mixed. For example, the presenter shows a slide listing three characteristics of viral conjunctivitis: conjunctival hyperemia, follicular reaction, and pre-auricular nodes. Then, another slide is presented, where these three features are shown in a picture. The same message can be transmitted efficiently and without redundancy using only the second slide.

VI. POSTURE

During a presentation, in addition to the quality of the material presented, it is necessary that the speaker gains the confidence of the audience. Then the message can be transmitted effectively. “Posture” refers to all actions that aim to attract the empathy and respect of the audience. Here are eight suggestions on the topic:

1. Respect the time. The lecturer should arrive at the venue of the lecture in time to resolve all issues that may occur, and begin the presentation on schedule. Delays are not well regarded. Furthermore, the time limit set for the lecture must never be exceeded because this may be considered a sign of neglect or disrespect.

2. Adhere to the theme. Do not stray from the subject. Presentations can be of various types: lectures, free discussions, and case presentations. Each of these has a specific objective and format. Classes convey concepts; free discussions often refer to scientific papers; and clinical cases present patient data for discussion. Therefore, it is essential that the presentation matches the format stipulated by the event. Failure to comply is likely to cause serious damage to the fluidity of the session and hinder the prestige of the offender. A typical violation is to take the opportunity of a case presentation to perform a literature review, which is only appropriate if this particular format was agreed upon previously.

3. Respect the language of the event. The slides should be translated into the language defined by the scientific committee of the event. International congresses usually set two or three languages. Whatever language is chosen, it is important that the language of the slides and that of the lecture are the same, for consistency. For example, lectures in Portuguese with slides in a foreign language suggest snobbery. The excuse that the slides are in English because they are part of a course taught in North America is not acceptable.

4. Avoid excessive use of foreign words. In a lecture given in Portuguese, there is no harm in using the English term “stop-and-chop,” a common phacoemulsification technique. It is an established term, and its translation does not bring practical advantages. However, the English terms “hinge,” “overcylinder,” “best sphere,” and “in the bag” can be perfectly translated into Portuguese, without losing the original meaning. There is no reason to use them in a foreign language. However, if foreign terms are utilized, it is paramount that they are pronounced correctly.

5. Focus on the whole. If the presentation is part of a sequence, such as a course, be careful not to repeat information provided by the preceding colleagues. Do not be repetitive. Skip the slides that have become redundant, explaining that the matter was already addressed within the current session.

6. Be a motivator. Recently, the cellist Yo-Yo Ma gave the following answer when asked regarding how he felt when he played for a full theater, “There is a magical line that separates the audience from the stage. The artist's job is to break this line and reach the hearts of the people.” Oral presentation is an art. Therefore, change the vocal tone and modulate it to highlight the important points, make hand gestures, move around in the room, and touch people's hearts.

7. Do not lose your temper. There are people who will interrupt the lecture to cause controversy. If space is given, they will ruin the lecture. The best way to get around this is to invite them, calmly and firmly, for a private conversation after the presentation.

8. Dress appropriately. Try to dress in accordance with the audience, as this will create a sense of affinity. Some meetings require jackets and ties, whereas others require casual dressing. Do not be deluded into thinking that formal attire is appropriate for all occasions.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

There are different strategies for the preparation of an oral presentation with slides.1-5 Find them on the Internet, using the expression “rules for slide presentation” in a search engine. This article aimed to present the basic concepts, the essence of the matter. As experience is gained, new and unexpected situations will arise that will require you to review your knowledge. Those revisions will improve your performance. However, there may come a day when it all appears to be useless. At that stage, you will be practicing the “philosophy of the long-haul driver.” Beware! You may have become a boring lecturer.

REFERENCES

1 Kelly PJ. The seven slide solutionTM: telling your business story in seven slides or less. Westport, CT: Silvermine Press; 2005.

2 Reimold C, Reimold P. The short road to great presentations. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-IEEE Press; 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/9780470546611

3 t Esposito J. In the SpotLight, overcome your fear of public speaking and performing. 3nd ed. Bridewater, CT: The Spotlight LLC/Strong Books; 2003.

4 Princeton Language Institute, Laskowski L. Ten days to more confident public speaking. New York, NY: Warner Books Inc; 2001.

5 Leech T. How to prepare, stage and deliver winning presentations. 2nd ed. New York, NY: AMACOM; 1993.

Funding source: None declared.

Conflict of interest: The author declares to have no conflicts of interest.

Research Ethics Committee Opinion: N/A.

Received on:

July 12, 2015.

Accepted on:

August 5, 2015.